SMIMIC Schedule

The San Marcos Informal Mathematics In-person Colloquium takes place every other Thursday, 12–1 PM, in Commons 206. Pizza is provided.Spring 2023

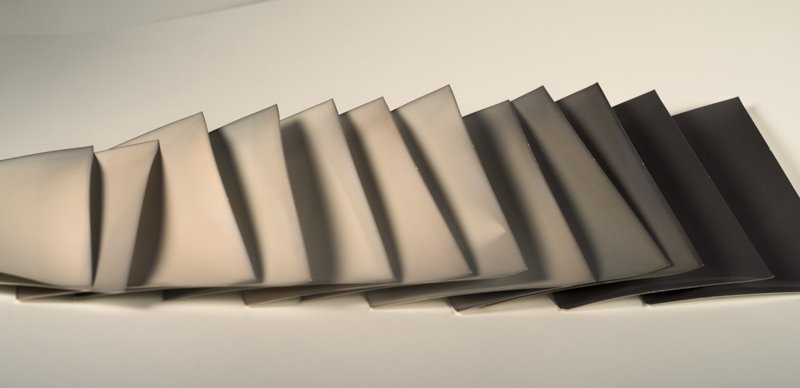

| 2/2 | Shahed Sharif, Mathematics of Origami, slides |

AbstractThrough hands-on demonstrations, we will explore the mathematics of origami. After remarks on how the theory of origami has historically unfolded, and the increasing use of origami in engineering, we will show how to trisect an angle with origami. |

|

| 2/16 | Everett Howe, Math from Medieval Musicians, slides |

AbstractAt the beginning of the 14th century, a music theorist and Catholic priest named Philippe de Vitry, who had been thinking about ratios of frequencies of musical notes, asked a question that nowadays we might phrase as follows: Which powers of 3 differ by 1 from a power of 2? Soon afterwards, his question was answered by a Jewish philosopher and mathematician named Levi ben Gerson. I will review some of this history, and show that in addition to ben Gerson's answer, there is a very elementary approach to de Vitry's question. This elementary approach allows us to answer much more difficult questions of a similar flavor as well. For example, using this method we can give a complete list of the powers of 3 that can be written in binary using at most twenty-two ones. |

|

| 3/2 | Mira Kündgen, Proofs from the book: counting trees |

AbstractIn 1860 Borchardt discovered a formula for counting the number of spanning trees of a complete graph. Many proofs of this result that has come to be known as Cayley’s formula are known. There are double counting proofs, bijection proofs, and proofs using linear algebra, among others. We will discuss 4 of these proofs. |

|

| 3/16 | Mary Pilgrim (SDSU), College Algebra Students’ Perceptions of Exam Errors and the Problem-Solving Process, Slides, Recording |

AbstractThe first two years of college play a key role in retaining STEM majors. This becomes considerably difficult when students lack the background knowledge needed to begin in Calculus and instead take College Algebra or Precalculus as a first mathematics course - courses associated with high failure rates. Given the poor success rates often attributed to these courses (Wakefield et al., 2018), researchers have been looking for ways in which to improve these courses, such as examining the impact of enhancing study habits and skills and metacognitive knowledge (e.g., Credé & Kuncel, 2008; Donker et al., 2014; Ohtani & Hisasaka, 2018; Schneider & Artelt, 2010). These efforts typically require students to reflect on the mistakes they made on exams. As part of a study on the impact of metacognitive instruction for College Algebra students (Pilgrim et al., 2020a), we found that students often attributed their exam errors to “simple mistakes” (Ryals et al., 2020b, p.494). However, we identified many of these as “not simple”. To understand students’ perceptions of their mistakes within the context of problem-solving, we adapted the Carlson and Bloom (2005) problem-solving framework as an analytical tool. We found that students’ and researchers’ classifications of errors were not aligned across the problem-solving phases. In this talk I will present findings from this work, sharing the adapted problem-solving framework, students’ perceptions of their exam mistakes, and the relationship between students’ categorizations of their errors and the problem-solving phase in which the errors occurred. |

|

| 3/30 | Paul Tokorcheck (USC), Writing Proofs With AI |

Abstract

The rise of artificial intelligence (AI) has led to a significant impact

on math education, especially in proof-based courses. This talk will

explore the various ways in which AI has influenced the teaching and

learning of mathematics, including automated grading, intelligent

tutoring systems, and computer-assisted proofs. |

|

| 4/13 | Gizem Karaali (Pomona College), Math … with a conscience? |

AbstractHistorian of mathematics Judith Grabiner tells us that mathematics in each culture solves problems that the culture thinks are important. In this framework, students of modern mathematics throughout our K-16 system learn that we value the bottom line, we value minimizing cost, we value precision in military applications. It is also quite clear that we are not concerned with equity issues, we are not interested in differences and dynamics of power, we are not going to touch social issues in our classrooms even with a very long pole. In this talk, I describe how this paradigm is changing in today's mathematics classrooms as well as in the broader mathematical community. The central question I address is: Does applicable math always side with the rich and the powerful? Or can it help us create a better, a more just world? I share some thoughts on how an intentional focus on the social and ethical dimensions of math starting from such questions can enrich the mathematical experiences of students at all levels of the curriculum and what it might mean to teach and do math for social justice. |

Fall 2022

| 9/8 | Hanson Smith, Richard Guy's Strong Law of Small Numbers and How Not to Make Friends |

AbstractThis talk will be a guided tour through Richard Guy's wonderful paper The Strong Law of Small Numbers. The main theorem is, "You can't tell by looking." Following Guy, we will prove this by intimidation. Audience participation, questions, and guesses are highly encouraged. We'll conclude the talk with an exciting application to web comics! |

|

| 9/22 | Shahed Sharif, SIKE Attack: How to Break Post-Quantum Crypto |

AbstractOver the past few years, the National Institute of Standards and Technology has been running a competition to standardize new cryptographic protocols which are safe from quantum computers. This past July, one of the top contenders, SIKE, was spectacularly broken. I will give an overview of the attack and explain the consequences. |

|

| 10/6 |

Mikaela Meitz, Hamiltonian Neural Network Exploration for Electron Particle Tracking Slides |

AbstractIn the field of accelerator physics, there is a burgeoning interest in using machine learning methods for aiding in the design and optimization of charged particle accelerators. The Advance Light Sources (ALS) at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory is a periodic circular accelerator called a synchrotron that emits ultraviolet and soft x-ray beams by accelerating electron bunches nearly as fast as the speed of light. These accelerators are prone to beam instability resulting in particle loss and consequently creating less x-ray brightness. The stability of an electron over thousands of revolutions is important to the performance of the accelerator. During these machines’ design or upgrade process, electron particle tracking is needed to ensure the particle dynamics are sufficient for the intended scientific use, but can be computationally expensive. If the dynamic aperture, the stability region of phase space in the synchrotron, is too small, then adjustments are made and the process is repeated until the desired result is achieved. Optimizing the dynamic aperture can require doing this tracking several times while iterating the accelerator design. Machine learning methods may alleviate some of the need for these expensive computations by making particle integration faster and easier to parallelize. This research explores electron particle tracking with the use of Hamiltonian Neural Networks. Machine learning based Hamiltonian Neural Networks (HNN) constrains the model learning to obey Hamiltonian mechanics so that the neural network can learn conservation laws from data. We compare the performance of HNN to other machine learning based models. |

|

| 10/20 | Kimberly Ayers, Baby Sharkovskii doo doo doo |

AbstractIt's time to get sharky—Sharkovskii, that is! Have you ever looked at the usual ordering on \(\mathbb{N}\), and thought, "I bet I can do better"? Well, Oleksandr Mykolaiovych Sharkovskii did just that in 1964 when he proved what is now called Sharkovskii's Theorem. This is Dr. Ayers's favorite theorem in the entire world. Come hear her talk about discrete dynamics, bifurcations, chaos theory, weird orderings on the natural numbers, graph theory, and even applications to candy making. |

|

| 11/3 | Sandie Hansen, Math on the Brain: Using Neuroscience to Better Understand How People Learn Math |

AbstractA human’s natural number sense first developed as a basic survival skill, but the abstract mathematics we teach in classrooms today is not. Using neuroscience and cognitive psychology research, we shall discuss why math is so hard for so many people and whether there is really such a thing as a "math person". The evolution of mathematics has exponentially outpaced that of the human brain, by studying the cognitive mechanisms involved in processing mathematical operations we will build a better understanding of how students learn math and we will consider how to adapt the math classroom using more brain-friendly methods. |

|

| 11/17 | Wayne Aitken, Filters and Ultrafilters |

Abstract

In calculus and especially in analysis we learn about a

plethora of types of limits: one-sided limits, two-sided limits, limits

of sequences, limits of functions, limits with finite values, limits

with infinite values, not to mention limsups and liminfs and limits of

"nets". What do these definitions of limits have in common? |